Table of Contents

IMAGINARY VOYAGES: SPACESHIPS AND MAN-BATS

|

In Caldecott winner Peter McCarty’s Moon Plane (Henry Holt and Company, 2006), a little boy watches an airplane in the sky – and then imagines flying it himself, over land and ocean, into outer space and to the moon. It’s a magical bedtime tale that ends with the boy’s mother tucking him into bed to dream of airplanes. For ages 2-6. |

|

In Ezra Jack Keats’s Regards to the Man in the Moon (Viking Juvenile Books, 2009), Louie is upset because the other kids call his father the “junkman” – until Louie’s dad shows him how junk plus imagination can become a fabulous spaceship. For ages 4-8. |

| Want a space ship of your very own? (And who doesn’t?) See How to Build a Cardboard Rocket Ship. | |

|

Hergé’s comic-strip hero Tintin is a young reporter who has exciting and far-ranging adventures in company with his faithful dog, Snowy, and a large cast of characters, among them the curmudgeonly Captain Haddock (of Marlinspike Hall), the brilliant and deaf (which makes for complications) Professor Calculus, and the bumbling, bowler-hatted detective duo Thomson and Thompson. There are 24 Tintin books in all, among them Destination Moon – originally published in 1953 – in which Professor Calculus joins a sabotage-ridden consortium attempting to land a man on the moon. In the sequel, Explorers on the Moon, Tintin and friends all blast off for the moon, pursued by villains, and saddled with stowaways Thomson and Thompson. |

|

Robert Heinlein’s Have Space Suit – Will Travel (Del Rey, 1985), originally written in 1958, features a bright high-school student, Kip Russell, who enters an advertising jingle contest in hopes of winning a trip to the moon. Instead, he wins a decrepit space suit – which he nicknames Oscar and manages to repair. He and Oscar then encounter a spaceship containing Peewee, an eleven-year-old girl genius, and her companion alien, a lemur-like creature from Vega known as the Mother Thing. All three are kidnapped by evil aliens, the Wormfaces, and taken to the moon, where they engineer a dangerous escape, and Peewee and Kip eventually end up on trial, struggling to save the entire human race. Sci-fi fans ages 11 and up will love it. |

|

In Robert Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (Orb Books, 1997), the moon is a former penal colony, still governed by a Warden, the representative of the Earth-based Authority, which now exploits lunar natural resources for huge profits. The oppressed natives (“Loonies”) – whose adaptation to the moon’s low gravity prevents them from ever returning to Earth – eventually rise in revolt, under the leadership of Mannie, the narrator, a one-armed computer technician, the elderly Professor Bernardo de la Paz (exiled to the moon for political subversion), the radical (and gorgeous) Wyoming Knott, and a newly sentient computer nicknamed Mike, who has a brilliant brain and a low taste in jokes. Thought-provoking and discussion-promoting. For ages 13 and up. |

|

H.G. Wells’s The First Men in the Moon (Dover Publications, 2000) is a sci-fi classic, originally published in 1901, in which the narrator travels to the moon with Mr. Cavor, a physicist, who has invented an anti-gravity spaceship-lifting substance called cavorite. There they are captured by the Selenites, an intelligent insectoid race that lives beneath the moon’s surface. The narrator eventually escapes, but Cavor is recaptured and stays behind, though he eventually manages to communicate with Earth by radio. When the Selenites discover humanity’s propensity for war, however, all broadcasts are cut off and Cavor is never heard from again. For ages 13 and up. |

|

M.T. Anderson’s chilling Orwellian novel Feed (Candlewick, 2004) begins when Titus and friends spend spring break on a trip to the nightclubs and shopping malls on the moon. In the world of Feed, people are given computer chip implants – “feeds” – in infancy, which continually bombard them with information in the form of pop-up advertisements. Mind-to-mind chats are the main means of communication; reading is obsolete; consumerism is rampant; and lifestyles are shallow and frenetic, punctuated with a Clockwork-Orange-like teenage slang. At the same time, corporations rule the world, the environment is polluted, and civilization is falling apart. Then Titus meets Violet, who becomes his girlfriend – a homeschooler who didn’t get her feed until she was seven. Violet is determined to resist the feed, a choice that ultimately leads to her destruction. A powerful book for ages 14 and up. |

|

Stephen Krensky’s The Great Moon Hoax (Carolrhoda Books, 2011) is a picture-book account of the famous hoax of 1835 perpetrated by a reporter for the New York Sun who, in a series of six exciting articles, claimed that astronomer John Herschel, using a new ultra-powerful telescope, had identified life on the moon. (Lunar Buffalo! Moon Beavers! Man-Bats!) The story is told through the eyes of two young newsboys, Jake and Charlie, with historical background on city life in the early 19thcentury. For ages 6-9. |

| The complete illustrated text of the original New York Sun articles, historical background, and commentary can be found at the Museum of Hoaxes website. | |

|

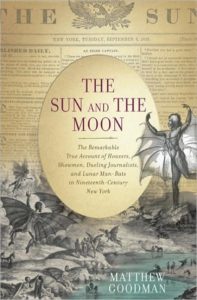

Matthew Goodman’s The Sun and the Moon (Basic Books, 2010) – subtitled “The Remarkable True Account of Hoaxers, Showmen, Dueling Journalists, and Lunar Man-Bats in Nineteenth-Century New York” – is a fascinating history of the Great Moon Hoax, covering the rise of tabloid journalism and the birth of science fiction, under the auspices of P.T. Barnum and Edgar Allan Poe. For older teenagers and adults. |

| From the New York Times, Giant Leaps of Moonstruck Dreamers is a short history of the moon in science fiction and how it inspired a generation of astronauts, rocket engineers, and astrophysicists. |